Sam and I have been searching for a way to get rid of time-outs. Who wants to reprimand their kids? Also, do time-outs really work? A new article on The Atlantic asked Alan Kazdin, director of the Yale Parenting Center, to give us parents some new tools instead.

The Atlantic: So what’s the short version of how to change behavior without punishment?

Kazdin: What it amounts to is an area of research that’s called applied behavior analysis, and what it focuses on are three things to change behavior: What comes before the behavior, how you craft the behavior, and then what you do at the end.

There are a whole bunch of things that happen before behavior and if you use them strategically, you can get the child to comply. Let’s say the child always just folds her arms and says, “no.” That’s not such a big deal, that’s actually easy to change, but a parent’s not going to be able to do it. They’re going to say, “you better do it because I say so,” or “we have to go,” or “you better do it now or I’m going to force this on you,” and that’s typical parenting.

So what comes before the behavior?

One is gentle instructions, and another one is choice. For example, “Sally, put on your,”— have a nice, gentle tone of voice. Tone of voice dictates whether you’re going to get compliance or not. “Sarah, put on the green coat or the red sweater. We’re going to go out, okay?” Choice among humans increases the likelihood of compliance. And choice isn’t important, it’s the appearance of choice that’s important. Having real choice is not the issue, humans don’t feel too strongly about that, but having the feeling that you have a choice makes a difference.

So now that’s what comes before the behavior.

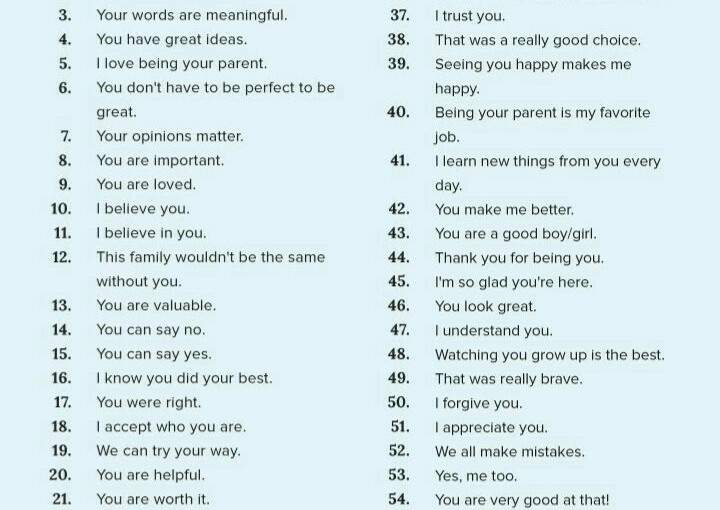

And now the behavior itself. When you get compliance, if that’s the behavior you want, now you go over and praise it … very effusively, and you have to say what you’re praising exactly.

And now, there’s a game:

I say, “We’re going to play a game and here’s how this goes: I’m going to tell you you can’t do something, but you really can, and you can have a tantrum and you can get mad, but this time you’re not going to hit mommy, and you’re not going to go on the floor. And it’s only game, but if you can do that, I’m going to give you two points on this little chart.”

So the mom leans over and smiles and whispers in this cute way, “Okay, Billy, you cannot watch TV tonight.” And Billy, have your tantrum, and don’t hit mommy or go on the floor.

[After the fake tantrum], the child is probably smiling a little bit and the mom says with great effusiveness, “That was fabulous! I can’t believe you did that!”

Getting the child to practice the behavior changes the brain and locks in the habit. And we’ve only done it once. So now we say to Billy, “Billy, I bet you can’t do it again. I don’t think there’s a child on the planet who can do this twice in the row.” Billy’s smiling and says, “No I can, I can do it,” and I say, “Okay, okay, we’ll do one more.”

Now you do this again and the same thing happens. If the tantrum has many different components, you change your requirement—this time, you don’t do whatever. You practice it, maybe once or twice a day, and you do this for a while.

As you do this every few days, now there’s a real tantrum that occurs outside the game. And that tantrum is either a little or a lot better. Now, you go over there and say, “Billy I can’t believe it, we weren’t even playing the game, and look at what you did, you got mad at your sister, but you didn’t hit anybody! Billy, that was fantastic.”

Think this will work? I like how it incorporates positive reinforcement.

The basic fundamental approach is, what is going on before the behavior that you can do to change it? Can you get repeated practice trials? Can you lock it in with praise? What happens is that parents think of discipline as punishing, and in fact, that’s not the way to change behavior.

0 comments